Rorschach tests play with the human imagination and our mind’s ability to impart meaning onto the world around us – but what does AI see in them?

For more than a century, the Rorschach inkblot test has been widely used as a window into people’s personality.

Even if you haven’t done one yourself, you’ll recognise the mirrored ink smudges that form ambiguous shapes on cards. Developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921, the test involves showing a number of inkblots to subjects, then asking them to say what they see. The images are deliberately inscrutable and open to interpretation.

For decades they were popular among psychologists as a way of understanding a person’s psyche from the creatures, objects or scenes they perceive in the shapes. It relies upon a phenomenon known as pareidolia, which is a tendency to find meaningful interpretations in things where there is none. It is the same reason why people see faces or animals in cloud formations or on the surface of the Moon.

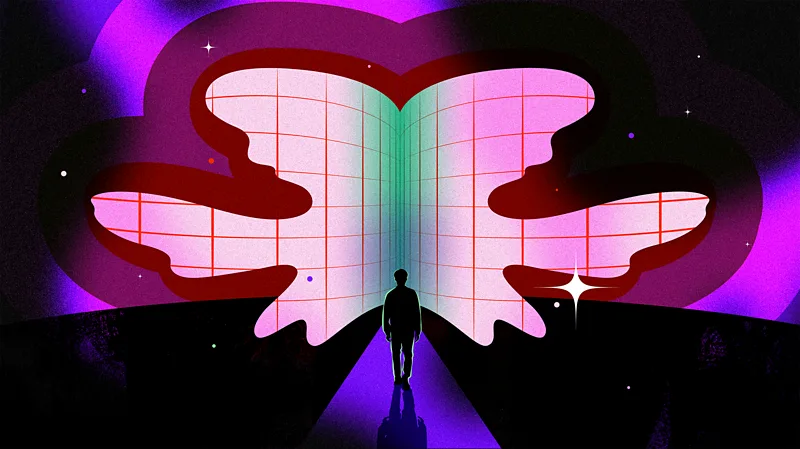

You might see a butterfly in the image while someone else might see a skull. According to proponents of the test, both interpretations shed light on how you think.

While many psychologists today believe the test is now obsolete and has little credibility as a psychometric tool, it is still used in some parts of the world and is even used as part of courtroom evidence, although this is controversial. Rorschach never intended it to be a measure of personality, but rather a way of identifying disordered thinking in patients, such as those with schizophrenia. Some psychologists, however, still believe it is useful as a tool in therapy as a way of encouraging self-reflection or starting conversations.

“When a person interprets a Rorschach image, they unconsciously project elements of their psyche such as fears, desires, and cognitive biases,” says Barbara Santini, a London-based psychologist, who uses the Rorschach test with her clients. “The test works because human vision isn’t passive, but a meaning-making process shaped by personal experience.”

Finding meaning or familiar shapes in inkblots relies upon a number of cognitive processes that humans use every day, including memory, emotion and the ability to deal with ambiguity.

But what happens if you have no personal experience, or you offer it to a “brain” that works in an entirely different way? What might an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm recognise in these inkblots? And what would their answers tell us about the human